Play By Email Week: Diplomacy

Before last year, the only Play By Email game I’d tried was Diplomacy. Following this blog’s standard practice of only reviewing things that are “new to me”, I won’t be officially grading this. However, it would earn an A or A- if I did, and I still want to talk about it because I think it’s the gold standard for how a PBEM game should work.

For those that don’t know, Diplomacy is a classic board game in which seven players fight over territory in pre-World War Europe. Every army is fairly weak on its own, so it’s important for players to make alliances to help each other. But the constantly-shifting strategic positions, as well as the zero-sum nature of the game, means that you’ll eventually have to break your promises and change alliances. Most of the game is spent with players simply talking to each other, and then they secretly write down orders that everyone turns in simultaneously. People either love or hate this game, as it’s long, intense, and gets players emotionally invested enough to take betrayal personally. Regardless of whether you like the game or not, anyone interested in email gaming should look at how online Diplomacy was implemented. There are two big reasons why I call this the standout for PBEM.

First of all, it’s amazing to see how much this changes when it’s played online instead of face-to-face. I said in my previous article that I’m not interested in email games that simply reproduce tabletop experiences, but I don’t think that’s the case here at all. For one thing, Diplomacy is complex enough that you could easily spend hours planning moves and negotiating with everyone, but typical games only allow fifteen minutes between turns to keep the game down to a single evening. It feels like a sprint that repeats itself every few minutes for hours. Over email, though, there are usually two or more days between turns. That’s enough time to plan and discuss extensively, even while going about your life. Even more importantly, though, face-to-face Diplomacy allows everyone to see who is talking to each other. You may not hear what they say, but you’ll know who may be planning to work together. Online, this is all hidden from others’ views, so you can talk to someone for as long as you want without making your current ally suspicious. In short, tabletop Diplomacy turns both time and conversations into a resource to manage, while email games take those out of the equation to let you focus on the core game. Neither is necessarily better or worse, but it’s fun to experience it both ways.

The second notable thing about PBEM Diplomacy is its implementation. This is written and hosted free of charge by fans, but it’s more reliable and feature-rich than commercial PBEM games. It may be because of its free nature that it’s so robust, because the hobbyists who run the servers don’t have time to handle anything manually. Everything, from requesting lists of open games or rules, to submitting your orders, can be handled with automated email codes. Even better, you’ll get an email back within seconds that tells you what you requested and whether or not you had typed in any errors. It even spells out details that the terse order codes don’t include, so it’s immediately obvious if you typed something wrong. Orders can be changed and errors corrected at any time before the turn deadline. Also, messages can be sent to other players through the system. This keeps the game anonymous if desired (since Diplomacy players try to avoid personal grudges), and lets you clearly identify players as “Italy” or “Russia” instead of “John” and “Dave”. When the game is anonymous, cheating is virtually impossible, because no one knows how to lie or spoof emails when they don’t know any other players’ addresses. These are all little things, but the make the system work very smoothly.

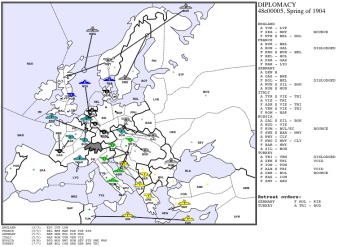

An example from a game I played, using an online mapping utility that helps visualize games on dozens of Diplomacy servers.

As fun as this is, though, I can only play every year or two. These games are too time-consuming and intense for me to stick with it more regularly. The standard two-day turnaround time forces you to put in significant effort every day. In addition to that, the game gives late players a grace period, so unexpected delays of hours or days will happen from time to time. Eventually, a late player will be kicked out, and the game will go on hold until someone new volunteers to take over the abandoned position. (And since it was probably abandoned because the player was losing, it usually takes a while before someone is willing to do so.) I think every game I’ve played has had a couple multi-week breaks because of this. This makes planning to play Diplomacy very difficult, because I don’t know what days over the next several months might be focused and busy and which days will have no gaming at all.

A great experience every couple years is still worth noting, though. Diplomacy’s email implementation is not only well-designed, but a fascinating study in the way environment changes a game’s mechanics.

Astronut

Astronut Pangolin

Pangolin

The first thing you’ll see when starting Might & Magic: Clash of Heroes is a warning that quitting the game at the wrong time will corrupt all saved game data. That’s just not an acceptable flaw for an iPhone game to have, and it’s the first sign that this Nintendo DS port may not have been planned very carefully.

The first thing you’ll see when starting Might & Magic: Clash of Heroes is a warning that quitting the game at the wrong time will corrupt all saved game data. That’s just not an acceptable flaw for an iPhone game to have, and it’s the first sign that this Nintendo DS port may not have been planned very carefully.

Even with a bigger screen, there would be other problems. The fights don’t become interesting until you gain a few levels and earn enough units to fill the battlefield. You need to wait for frequent load screens. Worst of all, the gameplay is slow, with the “minutes played” counter on the save screen feeling less like an interesting fact and more like a note about how much time you’ve wasted. Once your units are ready to attack, they take a certain number of rounds to charge up. This is important to the strategy, since you may use that time to set up combos, and your opponent may try to prepare with walls or by setting up a faster attack in the same column. However, it means that you may still have a few rounds left to play after the outcome of the battle becomes obvious. And the rounds play slowly. With the animations of each unit charging up or fighting and the slow-paced opponent moves, you’ll often need to tap your screen to keep it from falling asleep between the time you end one round and begin the next! That feels way too passive. By the higher levels (which you get to quickly, since the game is a series of campaigns), the no-risk battles against minions can easily take eight to ten minutes, and a battle featuring defense and healing abilities could feasibly take half an hour! They never feel meaty enough to justify that time.

Even with a bigger screen, there would be other problems. The fights don’t become interesting until you gain a few levels and earn enough units to fill the battlefield. You need to wait for frequent load screens. Worst of all, the gameplay is slow, with the “minutes played” counter on the save screen feeling less like an interesting fact and more like a note about how much time you’ve wasted. Once your units are ready to attack, they take a certain number of rounds to charge up. This is important to the strategy, since you may use that time to set up combos, and your opponent may try to prepare with walls or by setting up a faster attack in the same column. However, it means that you may still have a few rounds left to play after the outcome of the battle becomes obvious. And the rounds play slowly. With the animations of each unit charging up or fighting and the slow-paced opponent moves, you’ll often need to tap your screen to keep it from falling asleep between the time you end one round and begin the next! That feels way too passive. By the higher levels (which you get to quickly, since the game is a series of campaigns), the no-risk battles against minions can easily take eight to ten minutes, and a battle featuring defense and healing abilities could feasibly take half an hour! They never feel meaty enough to justify that time.

Juggernaut: Revenge of Sovering is an attempt to translate the feel of a big-budget video game to handheld devices. They found a lot of interesting ways to make the combination work, but main effect was to make me think about how the line between hardcore and casual gaming is a lot finer than most people think.

Juggernaut: Revenge of Sovering is an attempt to translate the feel of a big-budget video game to handheld devices. They found a lot of interesting ways to make the combination work, but main effect was to make me think about how the line between hardcore and casual gaming is a lot finer than most people think.