The 2011 Dominion Expansions(Game Review)

Dominion: Cornucopia and Hinterlands

Cornucopia and Hinterlands, the sixth and seventh releases of Dominion, have finally found the series reaching a point of diminishing returns for me. They are still great additions to the base game, but I’m at the point where I had enough Dominion cards already that these were “nice to haves”, not vital purchases. The main reason I’m only now getting around to discussing these 2011 releases is that I mixed them in with so many other cards that it became difficult to pick them out for specific review. Of course, your mileage may vary. Some people reached this point a few expansions ago, and others are still discussing the next release with the same eagerness I was using back in the Prosperity days. It’s probably telling, though, that Rio Grande is finally slowing down their schedule to one expansion per year.

Even if it arrived too late to feel vital, Cornucopia still adds fascinating new twists to the game. It’s only a half-sized release, the same size as the unloved Alchemy expansion, but this one is as interesting as a full-sized one. It turns a central tenet of Dominion on its head: One of the first hard lessons for new players is that buying every cool card available will lead to an unpredictable, diluted deck. Good players build a strategy around only a few Kingdom cards, sometimes as few as one. About half the cards in Cornucopia, though, reward you for owning a variety of cards. Whether it’s points for the “differently named” cards in your deck, coins for the different ones you played, or bonus draws as a prize for having no duplicates in your hand, they take varied approaches towards encouraging a wide-ranging strategy. A couple other cards actually increase the number of “named cards” available in a single game: The Young Witch is an attack that can be blocked by an extra “Bane” card in the supply (which is any random 2- or 3-cost Kingdom card), and the Tournament comes with five distinct “Prize” cards for players to win.

This turns out to work very well. Though varied decks are almost always weakened, they aren’t completely crippled. A minor boost in return for the variety can be enough to make it worthwhile. This means that a strategic approach that had almost always been weak in the past is now sometimes good and sometimes bad. This is exactly what makes Dominion such a great game: The new expansions neither fade into obscurity nor completely overpower the old cards. Instead, they open up new strategic avenues that hadn’t been considered in the past, while leaving the old ones available. It’s only the timing that keeps me from proclaiming Cornucopia to be a vital expansion; As it is, it still makes the game a richer experience.

Hinterlands, on the other hand, didn’t have that effect on me. This expansion’s theme is cards that have an effect as soon as you Buy or Gain them. While not completely new, it’s still a relatively unexplored area of the game that deserves more attention. However, one-time effects rarely feel as game-changing as abilities that can be used repeatedly, such as Cornucopia’s. Further, expanding this area of the game adds to the complexity of the rules. Do you understand the timing difference between “Buying” and “Gaining” a card? How does an ability that triggers “when you would gain another card” interact with the on-Gain effect of the card you would have gained? Don’t worry, the rulebook does explain these (with the typical thoroughness that other game publishers should learn from), but this is definitely a signal that Dominion is moving in a more complex, “experts-only,” direction. I don’t mind that in theory, but I wish the release that did this would feel at least as significant as the ones that came before.

That said, both of these are solid expansions to my favorite game. I can play this nearly one hundred times per year, and I’m still frequently surprised by how different one set-up can be from the next. Cornucopia only offered a taste of the paradigm-shaking changes of the early expansions, and Hinterlands mixed right in without any surprise, but they maintain the current level of quality and are the reason this game will still feel varied to me a year from now. If I sound a little cynical, it’s because I’ve reached the point where I understand why some people have Dominion fatigue. I still say these games are worth buying, though, and I’m confident that I’ll be standing in line for the next one.

Dominion: Cornucopia: B+

Dominion: Hinterlands: B-

This isn’t a Dominion clone. Kingdom Builder feels less like a Dominion knock-off than deck-builders such as Ascension and Thunderstone. Just as two very different Reiner Knizia games can both be recognized as having common elements, these two Vaccarino games share a similar approach. They deserve to be judged on their own merits, though.

This isn’t a Dominion clone. Kingdom Builder feels less like a Dominion knock-off than deck-builders such as Ascension and Thunderstone. Just as two very different Reiner Knizia games can both be recognized as having common elements, these two Vaccarino games share a similar approach. They deserve to be judged on their own merits, though.

The elevator pitch that I usually hear for Confusion is “It’s like Chess meets Stratego“. While this does cover a lot of the game’s basics, it’s also somewhat misleading. Because you can see what your opponent’s pieces can do instead of your own, it’s actually the opposite of Stratego. It will probably be easiest to show how the game works, and how cleverly the components support this structure, with pictures.

The elevator pitch that I usually hear for Confusion is “It’s like Chess meets Stratego“. While this does cover a lot of the game’s basics, it’s also somewhat misleading. Because you can see what your opponent’s pieces can do instead of your own, it’s actually the opposite of Stratego. It will probably be easiest to show how the game works, and how cleverly the components support this structure, with pictures. “Zeus has decided that he wants to construct a universe.” I hope you don’t need theme, because that’s about as much as The Heavens of Olympus ever provides. Over the course of five days (marked by the phases of the moon, for some reason), players are charged with placing planets in the sky in order to form constellations. (Yes, these constellations are made of planets.) Points are rewarded based on the fact that Zeus craves variety. In other words, the game’s rules have nothing to do with either actual cosmology or Greek myth.

“Zeus has decided that he wants to construct a universe.” I hope you don’t need theme, because that’s about as much as The Heavens of Olympus ever provides. Over the course of five days (marked by the phases of the moon, for some reason), players are charged with placing planets in the sky in order to form constellations. (Yes, these constellations are made of planets.) Points are rewarded based on the fact that Zeus craves variety. In other words, the game’s rules have nothing to do with either actual cosmology or Greek myth.

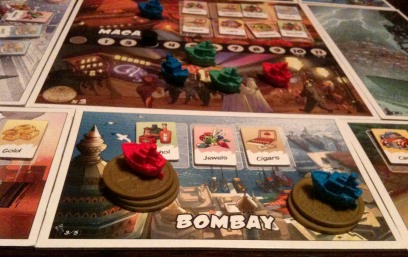

While bidding games are incredibly common in the current board gaming scene, Cargo Noir manages to find a new twist on the mechanic. Each turn, a player has a few ships that they can send out to offer money for a set of tiles. Those tiles won’t actually be purchased until the player’s next turn, which gives every other player a chance to make a higher offer on those same tiles. If the initial offer is outbid, the player who made it will need to either withdraw or raise their bid on their next turn. Because this is a new offer, it will be yet another time around the table before the tiles are actually won.

While bidding games are incredibly common in the current board gaming scene, Cargo Noir manages to find a new twist on the mechanic. Each turn, a player has a few ships that they can send out to offer money for a set of tiles. Those tiles won’t actually be purchased until the player’s next turn, which gives every other player a chance to make a higher offer on those same tiles. If the initial offer is outbid, the player who made it will need to either withdraw or raise their bid on their next turn. Because this is a new offer, it will be yet another time around the table before the tiles are actually won.

In some ways, a game that works for more than five people is the Holy Grail of the industry. In my opinion, even going past four people causes long delays between turns, and introduces too many factors that feel outside of a single player’s direct control. But when a group of friends gets together, it’s easy to end up with too many people to comfortably play one game, but not enough to split into two groups.

In some ways, a game that works for more than five people is the Holy Grail of the industry. In my opinion, even going past four people causes long delays between turns, and introduces too many factors that feel outside of a single player’s direct control. But when a group of friends gets together, it’s easy to end up with too many people to comfortably play one game, but not enough to split into two groups. 7 Wonders offers a decent amount of choices. You can earn points through cards, advancing your personal “great wonder” track, matching symbols, getting money, or having a stronger military than your neighbors. The “Guild” cards that appear at the end of the game even let you score points for how advanced your neighbors are in various categories! It’s impossible to excel in every area, but they are well-balanced enough that you can ignore any of those and still win the game.

7 Wonders offers a decent amount of choices. You can earn points through cards, advancing your personal “great wonder” track, matching symbols, getting money, or having a stronger military than your neighbors. The “Guild” cards that appear at the end of the game even let you score points for how advanced your neighbors are in various categories! It’s impossible to excel in every area, but they are well-balanced enough that you can ignore any of those and still win the game.